Tag: taiji

The Remarkable History of Xingyi Quan: From Merchant Roads to Martial Mastery

Understanding the Monastic Roots of Baguazhang

Introduction

Baguazhang (八卦掌), translated as “Eight Trigrams Palm,” is a Chinese internal martial art known for its distinctive circular movements and fluid footwork. While it is widely practiced today for both martial and health benefits, its origins are deeply rooted in monastic traditions, particularly within Daoist practices.

Historical Background

The development of Baguazhang is closely associated with Dong Haichuan (董海川), a 19th-century martial artist. Dong is credited with integrating various martial techniques he encountered during his travels with the Daoist practice of circle walking meditation. This synthesis led to the creation of Baguazhang as a formal martial art.

Circle Walking Meditation

Central to Baguazhang is the practice of circle walking, a method derived from Daoist meditation techniques. Practitioners walk along a circular path, maintaining specific postures and focusing on breath control. This practice serves multiple purposes:

- Physical Conditioning: Enhances balance, coordination, and flexibility.

- Internal Energy Cultivation: Promotes the circulation of qi (vital energy) throughout the body.

- Mental Focus: Develops concentration and mindfulness.

The circular motion reflects the Daoist understanding of natural cycles and the continuous flow of energy in the universe.

Monastic Influence

In monastic settings, particularly within Daoist temples, circle walking was more than a physical exercise; it was a spiritual discipline. Monks used this practice to align themselves with the principles of the I Ching (Book of Changes), which emphasizes the dynamic balance of opposites and the constant state of flux in the natural world.

Martial Applications

Beyond its meditative aspects, Baguazhang’s techniques are highly effective in combat scenarios. The art emphasizes:

- Evasive Footwork: Allows practitioners to maneuver around opponents strategically.

- Dynamic Striking: Utilizes palm strikes delivered from various angles.

- Continuous Movement: Maintains fluidity to adapt to changing situations during combat.

These principles make Baguazhang a versatile martial art, suitable for self-defense and adaptable to various combat situations.

Conclusion

Baguazhang stands as a testament to the integration of spiritual practice and martial prowess. Its monastic roots highlight the importance of internal development alongside physical training. Today, practitioners continue to explore Baguazhang not only as a means of self-defense but also as a path to personal growth and harmony with the natural world.

References

- Traditional Baguazhang Circle Walking and the Natural Way

- 12 Mother Postures for Bagua Circle Walking Training

- Circle-walking basics

For further exploration, consider visiting local martial arts schools or online platforms that offer instructional materials and classes on Baguazhang.

Understanding Taiji Yin Yang

Understanding the Difference Between Qigong and Neigong: A Deep Dive into Energy Practices

The heart-mind concept in Taoism and Taiji

In Taoism and Taiji (T’ai Chi), the concept of “heart-mind” (xin 心) is a fundamental and multifaceted idea that integrates cognitive, emotional, and spiritual aspects of human experience. Here’s an explanation of what heart-mind means within these traditions:

- Unified concept of heart and mind:

In Chinese philosophy, including Taoism, xin (心) refers to both the physical heart and the mind. Unlike Western philosophy, which often separates reason and emotion, the Chinese concept of heart-mind views them as interconnected and coextensive. This holistic approach considers thought and feeling as integrated aspects of human cognition and experience. - Center of cognition and emotion:

Traditionally, ancient Chinese believed the heart was the center of human cognition. The heart-mind is credited with various functions, including thinking, understanding, knowing, intention, emotions, and desires. This comprehensive view emphasizes the interplay between cognitive and affective processes in human experience and decision-making. - Cultivation and naturalness:

In Taoism, particularly as described by Zhuang Zhou (Zhuangzi), the heart-mind is seen as being influenced by social and environmental pressures. While Confucians advocated cultivating the heart-mind to develop moral virtue, Taoists like Zhuangzi considered this socialization potentially detrimental to one’s personal nature. Taoist philosophy often emphasizes allowing the heart-mind to align with the natural flow of the Tao rather than forcing it through artificial cultivation. - Emptiness and stillness:

In Taoist practice, including Taiji, there’s an emphasis on cultivating emptiness and stillness in the heart-mind. The Daodejing often describes the ideal state of the heart-mind as empty and still, which allows it to be attuned and responsive to the natural way (Tao). This concept is crucial in Taiji practice, where practitioners aim to quiet the mind and become more responsive to the subtle energies and movements within and around them. - Holistic involvement in practice:

In Taiji and qigong practices, the concept of heart-mind extends beyond just the cognitive aspects. It involves a full-body engagement, where the practitioner aims to achieve attunement and responsiveness to the world through the entire system of qi (vital energy) that pervades all organs, not just the heart-mind. This holistic approach is evident in the fluid, meditative movements of Taiji. - Path to happiness and self-cultivation:

Some Taoist and Confucian thinkers, like Mencius, describe xin (heart-mind) as a way of returning to happiness. In Taiji practice, cultivating the heart-mind is seen as a path to personal growth, health, and harmony with the Tao. - Fasting of the heart-mind:

An important Taoist concept related to the heart-mind is “xin zhai” (心斋), or “fasting of the heart-mind”. This practice involves purifying and calming the self by refraining from excessive thinking and desire. It emphasizes the importance of quieting the mind to connect with one’s true nature and the Tao. - Thinking through the heart and feeling through the mind:

In Taoist philosophy and Taiji practice, there’s an emphasis on “thinking through the heart and feeling through the mind”. This approach encourages using the mind as an observation tool without judgment, while allowing the heart to provide direction. Meditation and Taiji are seen as ways to quiet the mind and hear the heart’s wisdom.

In conclusion, the concept of heart-mind in Taoism and Taiji represents a holistic understanding of human cognition, emotion, and spirituality. It emphasizes the integration of thought and feeling, the importance of naturalness and emptiness, and the cultivation of a state of being that is in harmony with the Tao. This concept is central to the philosophy and practice of Taiji, informing its meditative movements and approach to self-cultivation.

Sources:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xin_%28heart-mind%29

[2] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-mind/

[3] http://www.heartmind-taichi.com

[4] https://www.cafeausoul.com/iching/way-of-tao/tao-and-masters/xin-and-heart-mind

[5] https://heart-mind-tai-chi.com

[6] https://www.reddit.com/r/taoism/comments/155j161/mind_xin_%E5%BF%83_heartmind_in_chinese_philosophy/

[7] http://www.heartmind-taichi.com

[8] https://purplecloudinstitute.com/%E5%BF%83%E6%96%8B-xin-zhai-the-fasting-of-the-heart-mind/

[9] https://patrickkellytaiji.com/taiji/taijiprinciples.html

[10] https://www.taiflow.com/blog/seeing-through-the-heart-and-feeling-through-the-mind

[11] https://heartmindtaichi.org/taichi/

[12] https://wijsheidsweb.nl/wijsheid/heart-mind-and-psychology-in-ancient-china/

[13] https://heartmindcentre.com.au/tai-chi/

[14] https://www.chinesethought.cn/EN/shuyu_show.aspx?shuyu_id=2137

[15] https://heart-mind-tai-chi.com/contemplations/thoughts/An_Introduction_to_the_heart-mind/

[16] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11712-019-09686-z

(Internal) Chinese Martial Arts Manuals

The Stillness Within

The History of Taijiquan

Key Martial Artists in the Development of Taijiquan

The early development of Taiji, also known as Tai Chi Chuan, is deeply rooted in the martial arts traditions of the Chen family from Chenjiagou (Chen Village) in Henan Province, China.

The evolution of Taiji can be traced back to Chen Wangting, a 17th-century martial artist who is credited with creating several Taiji routines after his retirement from military service. He incorporated various martial arts techniques with Daoist philosophy, laying the foundational framework for what would later become known as Taiji.

Chen Changxing, a 14th generation descendant of the Chen family, played a pivotal role in the evolution of Taiji during the early 19th century. He synthesized earlier Chen routines into two routines known as the Old Frame (Laojia), which includes the First Form (Yilu) and the Second Form (Erlu or Cannon Fist).

Breaking with tradition, Chen Changxing taught these forms to Yang Luchan, a non-family member, who later popularized the style throughout China as Yang-style Tai Chi Chuan.

Chen Fake, a direct descendant of Chen Changxing, significantly influenced Taiji’s 20th century development. Born in 1887, he moved to Beijing in 1928 where he demonstrated Chen-style’s effectiveness through challenges, establishing its reputation. Chen Fake created the New Frame routines by adding movements to the Old Frame, emphasizing smaller circular motions, more obvious spiraling of the waist/dantian, explosive fajin (energy release) techniques, jumping footwork, and greater emphasis on martial applications like qinna (joint locks). The New Frame showcased a more dynamic and overtly powerful expression tailored to the “temperament of the young and fit city people” he taught in Beijing, while still adhering to Chen principles of continuous flowing movement.

Chen Qingping, another key figure, was a contemporary of Chen Fake and a 7th generation master of Chen-style Taiji. He is also associated with the development of the Zhaobao style of Taiji, having moved to Zhaobao Village and married into a local family. Chen Qingping’s teachings influenced the Zhaobao style, which shares similarities with the Chen style but also features distinct elements like the emphasis on spiral movements and uprooting techniques.

In summary, the development of Taiji from Chen Wangting through Chen Changxing to Chen Fake and Yang Luchan illustrates a rich history of innovation and adaptation within the martial arts.

Click on the map below to learn more about the individuals.

(work in progress, more articles will be added shortly)

Chen Fake

The Art of Taiji Sung (Taiji Song)

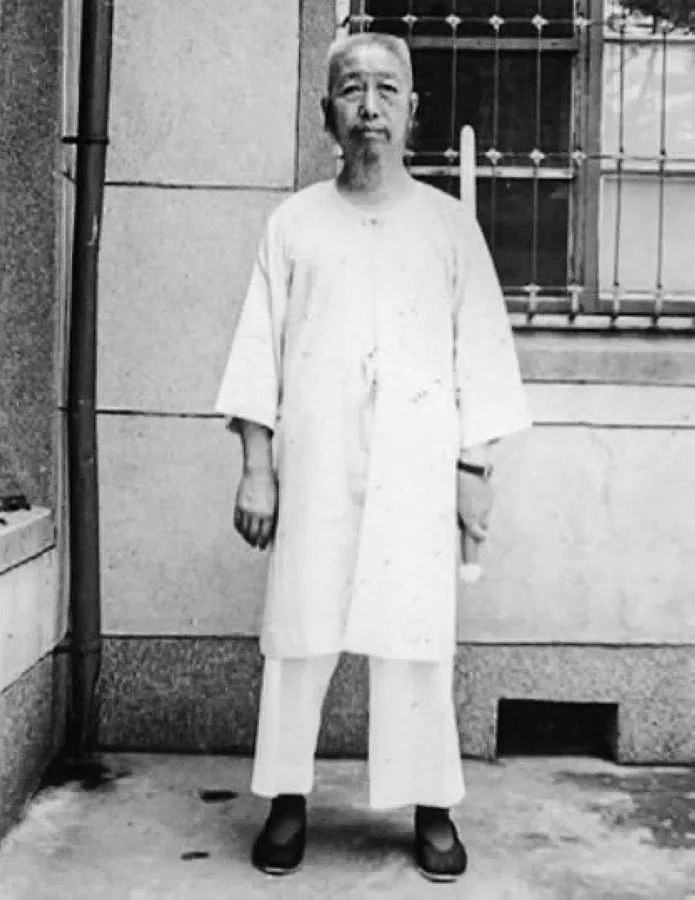

Cheng Man Ching

A Multifaceted Master of Taijiquan and Traditional Chinese Culture

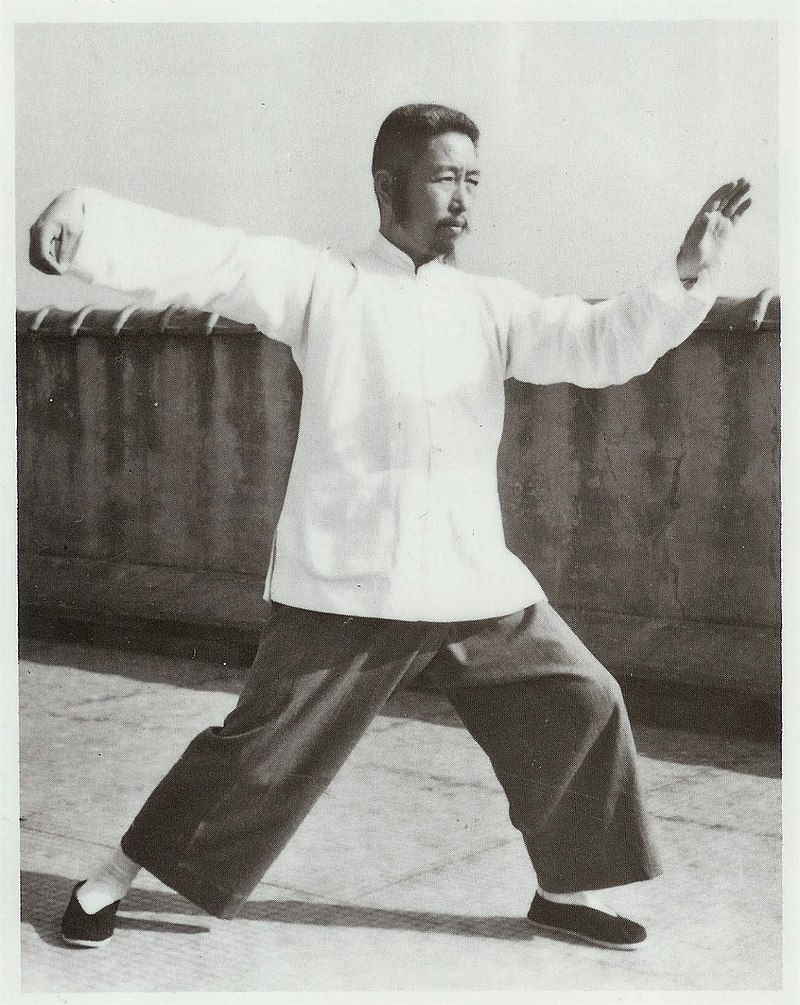

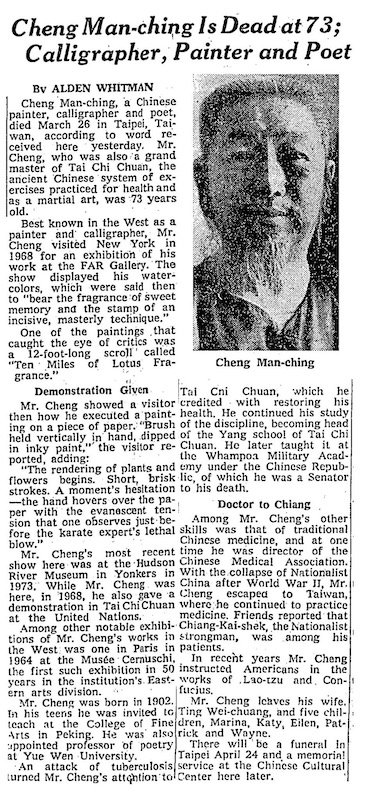

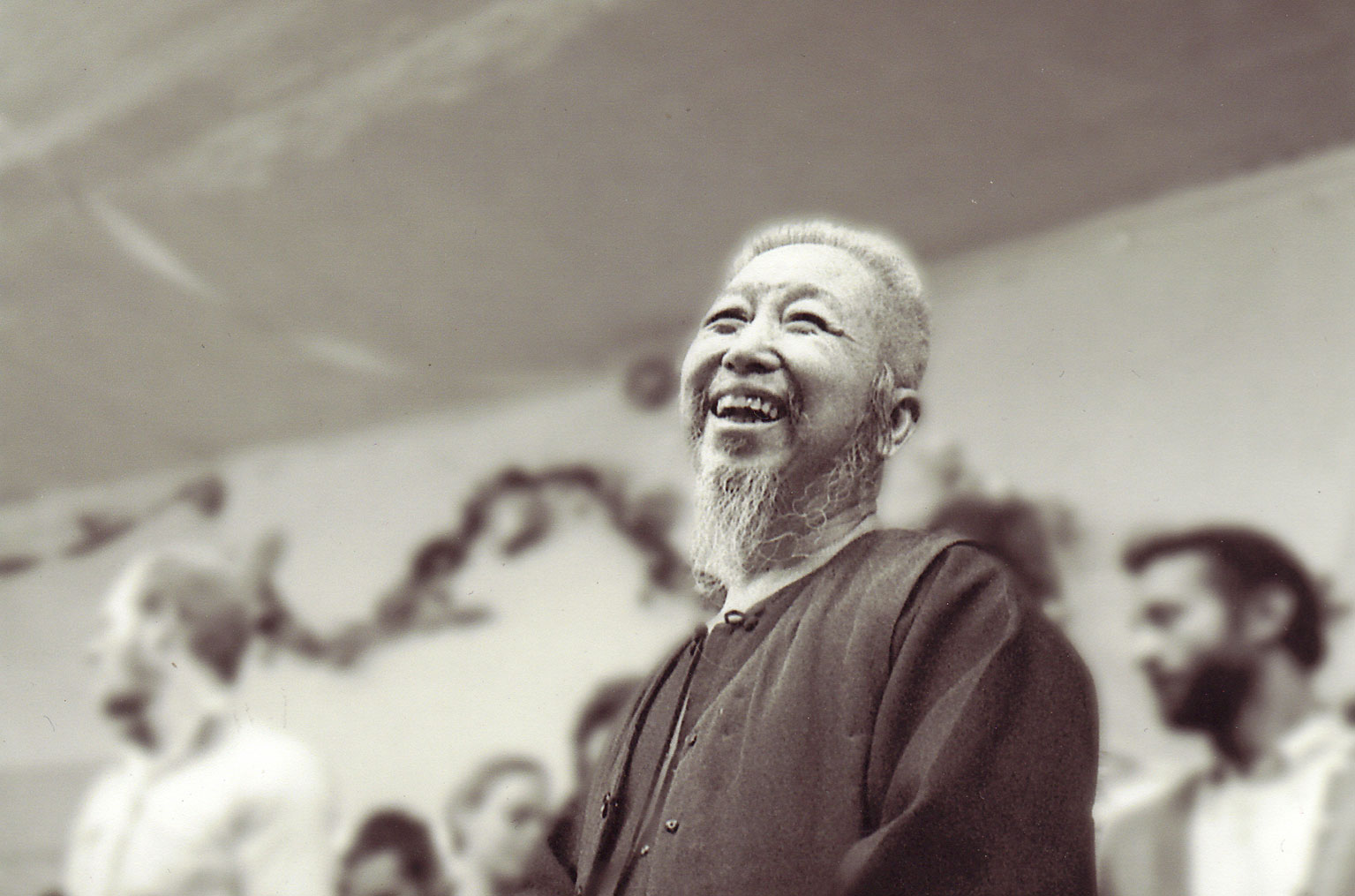

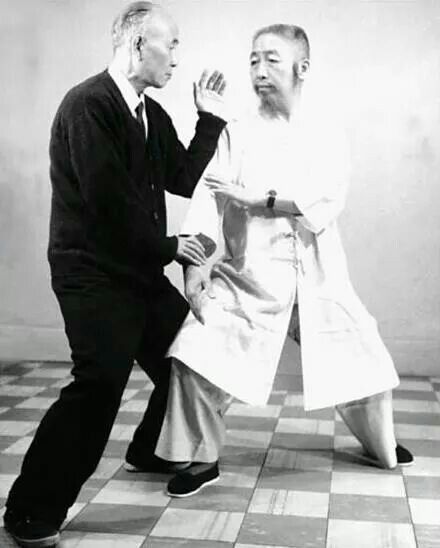

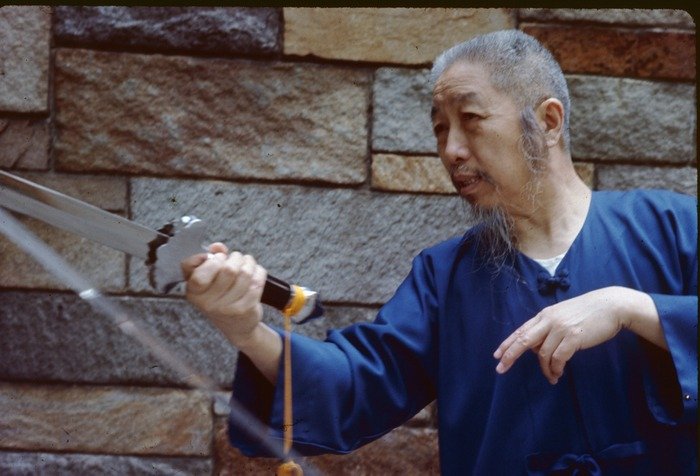

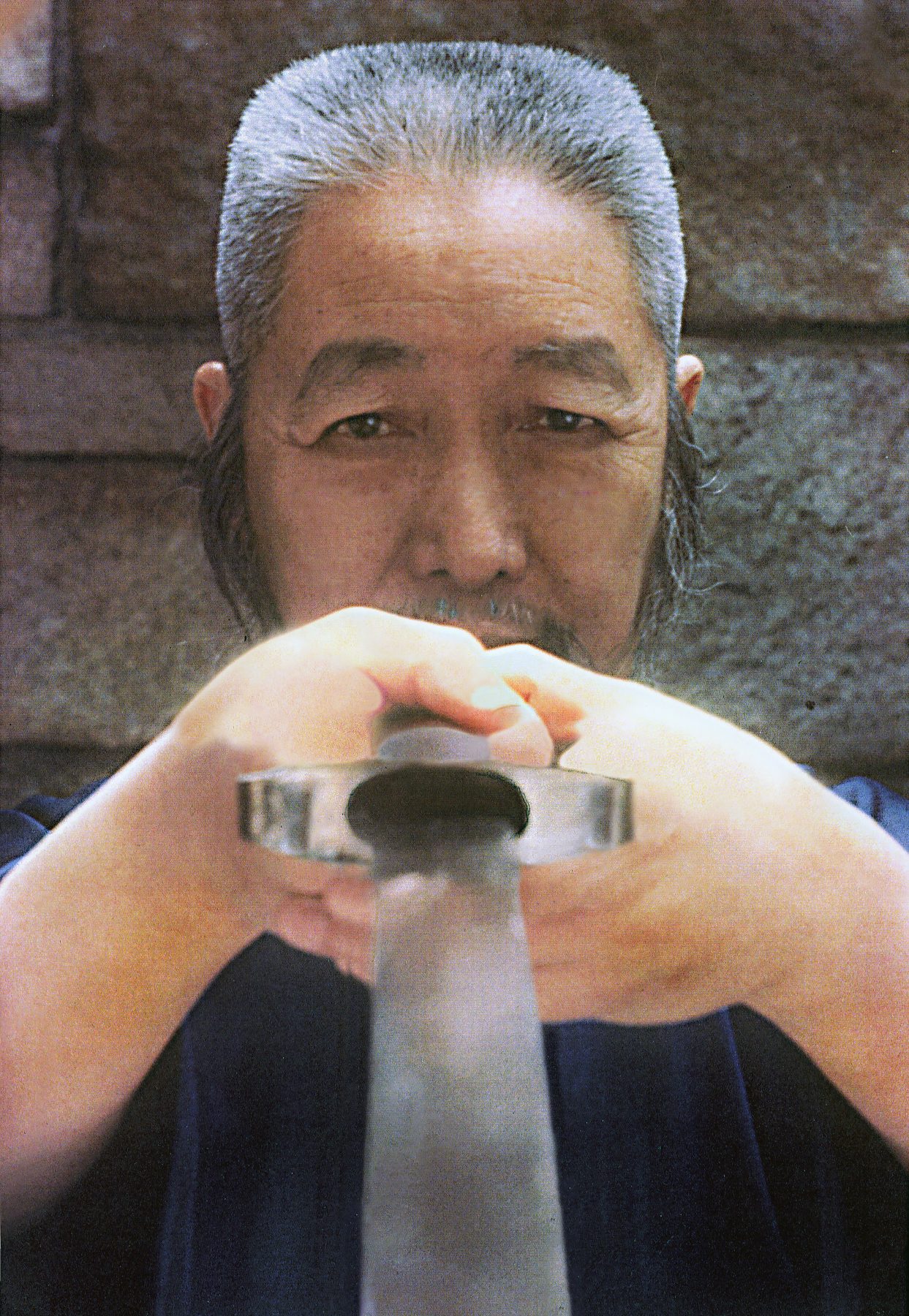

Cheng Man Ching, also known as Zheng Manqing, was a renowned figure in the realm of martial arts, particularly in Tai Chi Chuan, as well as a skilled calligrapher, painter, and doctor of traditional Chinese medicine. Born on July 29, 1902, in Yongjia County, Zhejiang Province, China, Cheng Man Ching’s life journey would leave an indelible mark on the world of martial arts.

Cheng’s introduction to martial arts began in his youth, studying under Yang Chengfu, the grandson of Yang Luchan, founder of the Yang-style Tai Chi Chuan. Cheng showed exceptional talent and dedication, mastering the art under Yang’s guidance. His understanding of Tai Chi Chuan went beyond mere physical movements; he delved deeply into its philosophical and spiritual aspects, a trait that would characterize his teachings later in life.

In addition to his martial pursuits, Cheng Man Ching was a polymath with diverse interests. He received formal education in traditional Chinese medicine and became a licensed doctor. His expertise extended to calligraphy and painting, where he gained recognition for his masterful brushwork and artistic sensibility.

Cheng’s life took a significant turn when he moved to Taiwan in 1948 amid the Chinese Civil War. There, he continued to teach Tai Chi Chuan, attracting a devoted following. He adapted the traditional Yang-style Tai Chi Chuan into a shorter, more accessible form comprising 37 postures, known as the Yang-style Short Form or Cheng-style Tai Chi Chuan. This innovation made Tai Chi Chuan more approachable to beginners while retaining its essence and effectiveness.

Throughout his teaching career, Cheng emphasized the health benefits of Tai Chi Chuan, promoting it as a holistic practice that nourishes both body and mind.

His teachings attracted students from diverse backgrounds, including martial artists, scholars, and health enthusiasts. Cheng’s reputation as a Tai Chi master grew, earning him the respect and admiration of practitioners worldwide.

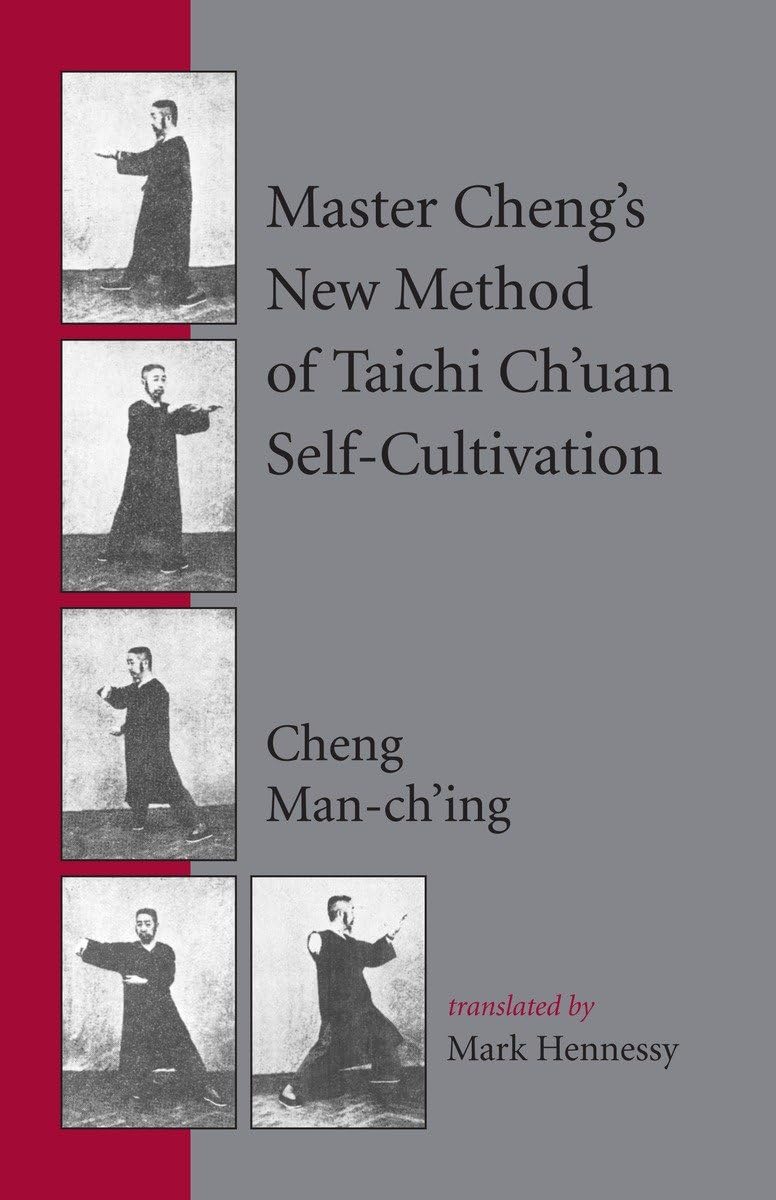

Cheng Man Ching’s contributions to Tai Chi Chuan extended beyond his innovative teaching methods. He authored several influential books on Tai Chi philosophy, including “Tai Chi Chuan: A Simplified Method of Calisthenics for Health & Self Defense” and “The Essence of T’ai Chi Ch’uan: The Literary Tradition.” These works helped popularize Tai Chi Chuan beyond China, introducing it to a global audience.

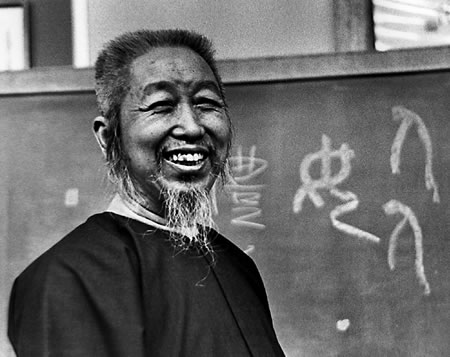

In his later years, Cheng Man Ching relocated to New York City, where he continued to teach and spread the practice of Tai Chi Chuan. He founded the Shr Jung School of Tai Chi Chuan, where he trained numerous instructors who would carry on his legacy. Despite battling health issues, Cheng remained dedicated to his practice and teaching until his passing on March 26, 1975.

Cheng Man Ching’s impact on Tai Chi Chuan cannot be overstated. He played a pivotal role in modernizing and popularizing this ancient martial art, transforming it into a widely practiced form of exercise and meditation. His teachings continue to inspire generations of practitioners, shaping the way Tai Chi Chuan is understood and practiced worldwide. Cheng’s legacy as a master martial artist, scholar, and healer endures, ensuring that his contributions to the world of martial arts and holistic health will be remembered for years to come.

Early Influences

Cheng Man Ching’s formative years were steeped in the traditions of Chinese art and culture. Raised in a family of artists, he inherited a deep appreciation for poetry, painting, calligraphy, and the nuanced principles of Chinese medicine. Despite the upheavals of early 20th-century China, Cheng’s artistic upbringing instilled in him a profound reverence for the interconnectedness of nature, body, and spirit – a theme that would resonate throughout his life’s work.

Philosophy and Way of Life

At the heart of Cheng’s teachings lay a profound philosophy that transcended the boundaries of martial arts. Rooted in the wisdom of ancient Chinese sages, Cheng espoused a holistic approach to life – one guided by principles of balance, harmony, and mindfulness. His famous dictum, “Use four ounces to deflect a thousand pounds,” encapsulated his belief in the power of skillful technique, inner strength, and non-aggression – a philosophy that resonated deeply with his students and admirers alike.

Legacy and Influence

Cheng Man Ching’s impact extends far beyond the realm of martial arts. Through his writings, teachings, and personal example, he inspired generations of practitioners to embrace Taijiquan as a path to holistic wellness and self-discovery. In the 1960s, Cheng brought Taijiquan to the West, igniting a wave of interest that continues to ripple across the globe. His “Cheng Man-ching Short Form” became a staple of Taijiquan practice in the West, admired for its elegance, efficiency, and accessibility.

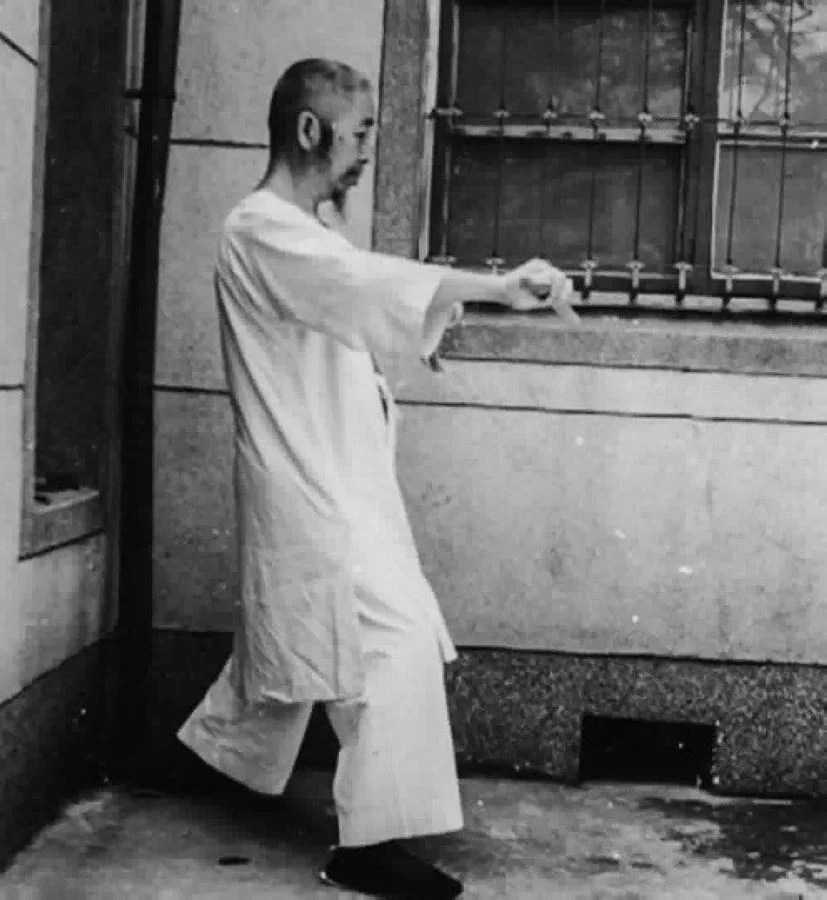

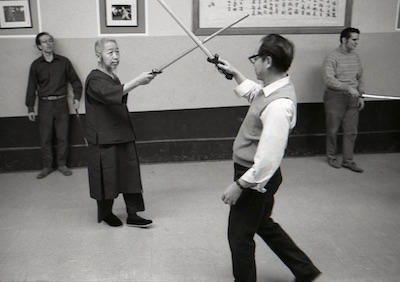

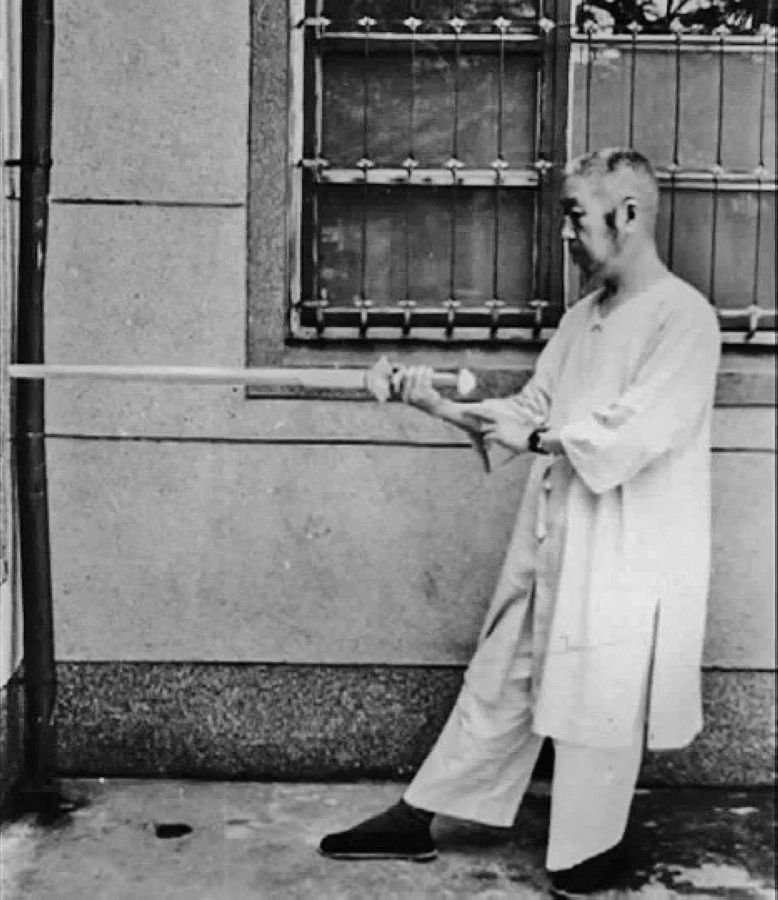

Tai Chi as Martial Art

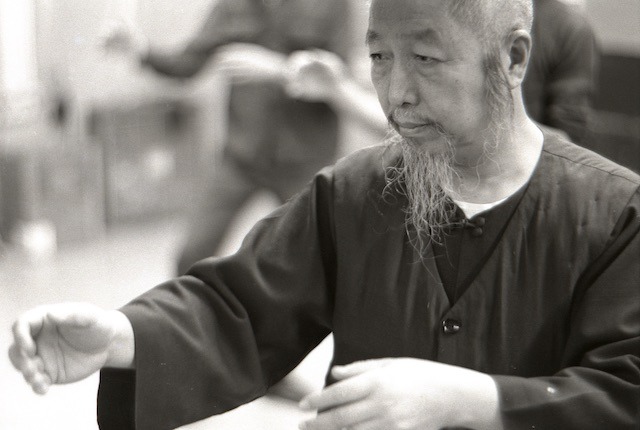

Central to Cheng Man Ching’s teachings was his nuanced understanding of Taijiquan as both a martial art and a holistic practice. While many view Tai Chi primarily as a gentle form of exercise, Cheng emphasized its roots in combat and self-defense. Drawing from his martial lineage and deep knowledge of Taijiquan principles, Cheng integrated martial applications into his teaching, offering students a comprehensive understanding of Tai Chi’s martial aspects alongside its health benefits.

For Cheng, the practice of Taijiquan was a dynamic interplay of Yin and Yang, softness and strength – a manifestation of Daoist philosophy in motion. Through his emphasis on proper body mechanics, sensitivity training, and the cultivation of internal energy, Cheng sought to impart not only self-defense skills but also a profound awareness of the body’s innate wisdom and potential for transformation. In essence, Cheng Man Ching’s approach to Taijiquan transcended the dichotomy of martial art versus exercise, inviting practitioners to explore the rich tapestry of Tai Chi as a holistic path to self-mastery and inner peace.

Books by or on Cheng Man Ching

Click on the book cover to go to Amazon to purchase the book. Please note that these are affiliate links, which means I get a small kick-back for the recommendation while your price stays the same. This helps me maintain this website. Thank you.